Finding the right product designer for your startup can feel like searching for a needle in a haystack. There are designers everywhere, and no matter how strong a resume or portfolio seems on the surface, it's often hard to tell whether they're truly the right fit until they actually start work. Here's why:

- Most designers work within existing design systems, so it can be hard to tell how much of their portfolio's visual design they're really responsible for

- Most designers don't work independently, so past work in their portfolio may actually be the result of collaboration between multiple designers

- A lot of designers include work that draws heavily on templates from popular libraries like Untitled UI or Shadcn

- Many portfolios are just modified templates from website builders like Framer or Webflow, which do most of the heavy lifting

- Job titles are used inconsistently across the industry, so it can be hard to disambiguate how much of their experience is directly relevant

- In some cases, designers simply pass off their team's work as their own

So given these challenges, how do you actually hire a UX designer, UI designer, or product designer who'll move the needle for your startup? This guide will walk you through how to properly screen and interview product designers to dramatically improve your chances of finding the right fit.

Step 1: Identify the Right Skillset

One of the biggest challenges is finding the right type of product designer. This challenge is perpetually exacerbated by design's evolving role and attempts to address the semantic gap. From Human Factors Engineers in the 50s to Information Architects in the 90s to experience designers in the 2000s to product designers in the 2010s—with many more in between—design is a role that continues to evolve and redefine itself. For a more recent example, see Duolingo's design org's recent rebrand from "UX" to "Product Experience".

To determine the appropriate role for your needs, you must first identify the specific skillset you need.

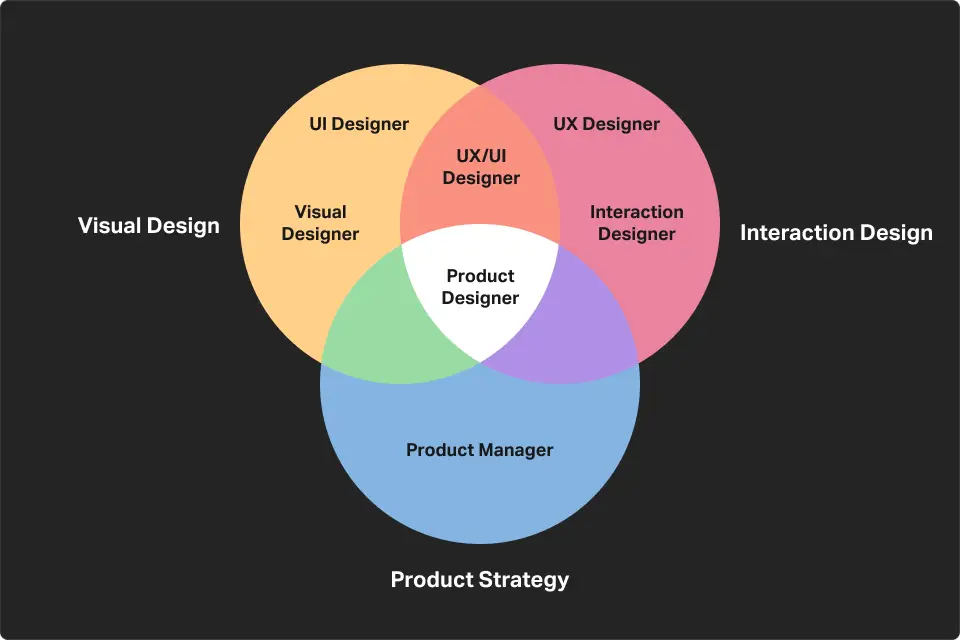

At the risk of being reductive, and without adding the complexity of voice or neural interfaces, the work of digital product designers today typically focuses on three core skillsets:

Visual Design — crafting the look and feel of a product; including defining typography, color, layout, visual hierarchy, spacing, iconography, etc.

Interaction Design — crafting how users engage with and navigate through a product; including conducting user research, mapping user journeys, defining information architecture, optimizing user flows and interaction models, etc.

Product Strategy — driving product strategy from ideation to launch; including identifying problems to be solved, ideating and prioritizing features, specifying requirements, defining success metrics, validating outcomes against those metrics, etc.

Depending on your product stage, industry, and current team, you may have wildly different needs across these skillsets. For example, if your engineering team is using a high-quality off-the-shelf UI library, then you may not have much need for visual design. Or if you already have a solid product team, you may not need more expertise in product strategy. Yet if you're a first-time solo founder, then you may benefit most from a generalist product designer who has experience across all three.

Whatever your situation, it's important to audit your current needs against your team's skillset to identify which gaps you need to cover with your design hire.

Step 2: Draft a Matching Job Description

The job title and description for the role should match the combination of skillsets identified in step 1.

If you only need visual design, the title should be "Visual Designer" or "UI Designer". If you only need interaction design, the title should be "Interaction Designer" or "UX Designer". If you need visual design and interaction design, the title should be "UX/UI Designer" or "UI/UX Designer". If you need all three, the title should be the generalist "Product Designer".

As for the role responsibilities, it's typically easiest to find an existing job description matching the relevant title. For a specialist role, Google's Visual Designer and Interaction Designer job descriptions are a good starting point. Note how the responsibilities are largely focused on a single skillset—in this case, interaction design:

- Collaborate with product managers, engineers, and cross-functional stakeholders to understand requirements, and provide creative, thoughtful solutions.

- Communicate the user experience at various stages of the design process with wireframes, flow diagrams, storyboards, mockups, or fidelity prototypes.

- Integrate user feedback and business requirements into ongoing product experience updates.

- Advocate for the prioritization of design centered changes, refinements, and improvements.

For a generalist role, Meta's Product Designer job description is a good starting point. Note how the responsibilities span across all three of the skillsets above:

- Take broad, conceptual ideas and turn them into something useful and valuable for our 2 billion plus users

- Design flows and experiences that simplify and distill down complex actions into usable interfaces

- Design new experiences or layouts that evolve and define visual systems

- Contribute to strategic decisions around the future direction of Facebook products

- Give and solicit feedback from designers and a broader product team in order to continually improve for quality

- Drive a partnership with product managers, engineers, researchers and content strategists in order to oversee the user experience of a product from conception until launch

- Willingness to represent work to a broader product team and other leaders, clearly and succinctly articulating the goals and concepts.

These examples should only be a starting point—the job description should always be tailored to the specific role. Simply copy-pasting a random product design job description, or having ChatGPT generate one, may save you 30 minutes now—but you'll likely waste more than that filtering through the unqualified applicants who apply based on a misleading job description.

Step 3: Post the Job Description

For most product design roles, you can't go wrong with posting on LinkedIn and Indeed. However, for generalist roles, it's also worth posting on Wellfound or Toptal. For visual design specialist roles, it's also worth posting on Dribbble or Behance.

In my experience, you're generally better off avoiding platforms like Fiverr and Upwork, as the results can be pretty inconsistent, and you'll often end up with more design debt than it's worth. If you want to go the cheap route, skip hiring entirely, and learn how to throw something together in Figma using a pre-built UI library.

Step 4: Conduct an Initial Screen

Once the applicants start rolling in, you should screen each individual's resume and portfolio to decide who will progress to a full interview loop. The screening criteria here will, like the job description, depend on the skillsets identified. However, here are some high-level suggestions to help you screen more effectively:

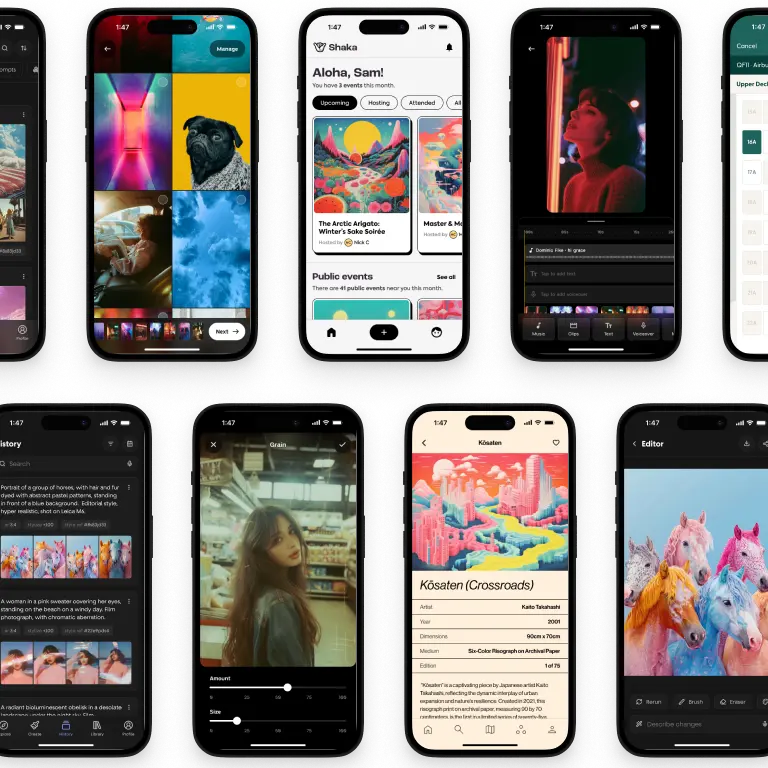

The portfolio design itself matters. The design of the portfolio itself should be considered part of the portfolio. This means the typography, color, and layout of the portfolio should be considered like any project presented within it. This can be very telling, especially when the projects themselves are from larger companies, where they're likely to be the result of collaboration between multiple designers.

Portfolio format signals technical ability. The format of the website can be an indication of the designer's technical skillset and soft skills, like personal drive and intentionality:

- The best, although rarest, format is a hand-coded custom website. This demonstrates solid technical understanding (which typically translates into better working relationships with engineering), and signals a solid level of self-motivation and intentionality.

- The next best would be a custom website built in an editor like Webflow. These usually indicate at least a foundational understanding of working with components and variables, and require more effort than editing a template.

- Next are drag-and-drop templates built with high-level tools like Squarespace. This is the most common approach for product designers. Although this isn't a red flag, these tools limit the breadth of customization available, and thereby deprive designers of another chance to demonstrate their skillset.

- With the limited exception of visual design specialists, using Dribbble or Behance as a portfolio is usually a red flag. If someone is designing for web or mobile experiences, they shouldn't be presenting their work as a single rasterized image, and forgoing the opportunity to demonstrate even a basic understanding of web design.

- Similarly, PDF portfolios are usually a red flag, and may indicate a lack of technical understanding. These are better suited to graphic designers.

Avoid process theater. Some designers like to flesh out case studies with dozens of photos of themselves whiteboarding and sketching user flows that are too small to read. These case studies are not correlative with better process or intentionality, and seem to be an odd artifact perpetuated by bootcamps.

Look for clear problem statements. Case studies should index around a clear problem statement—that is, they should articulate what problem the product is solving for users, and explain how their work helped solve that problem.

Success metrics matter. Case studies should include a clear definition of success. This will usually take the form of validation metrics, such as user engagement or conversion rates.

Check for design thinking fundamentals. Case studies should demonstrate that the designer follows a divergent-convergent design process. This means they should show that the designer considered a range of options—such as different component variants—then converged on a single solution based on testing or research. This is the foundation of design thinking, and its absence is a red flag. This is more important than covering an arbitrary checklist of information architecture diagrams, user flows, and personas.

No portfolio is a red flag. The absence of a portfolio is a red flag, and there is rarely, if ever, a valid reason for this. Where designers have only worked on commercially sensitive or NDA-covered work, they will still usually have a shell portfolio—one that only includes a high-level summary of projects, or indicative mockups to represent those projects.

Step 5: Conduct a Full Interview Loop

Types of Product Design Interviews

Once you've screened applicants, it's time to conduct a more comprehensive interview loop. In addition to standard behavioral interviews, there are several options for screening product designers' hard skills. A full structured interview loop will typically include a combination of the following:

- Portfolio Presentation — A review of the candidate's past work. This usually includes one to three case studies, which should be presented as a structured narrative.

- Take-Home Design Challenge — This is usually an alternative to a portfolio presentation for more junior designers who may not have enough experience to have a fleshed out portfolio.

- App Critique — Walking through a popular app together to evaluate design decisions and identify improvement opportunities.

- Whiteboarding Challenge — An open-ended problem-solving exercise that reveals how candidates approach complex design challenges.

We'll review each of these in more detail, noting which skillsets each are best aligned to screening for. For most roles, you'll use a combination of the Portfolio Presentation, App Critique, and Whiteboarding Challenge. However, for visual design specialist roles, you'd be fine with just the portfolio presentation and app critique.

Portfolio (Past Work) Presentation

Suitable for: Visual Design, Interaction Design, Product Strategy

Ask candidates to present one to three case studies that best demonstrate the skillsets you've identified. This can be structured either as a 30-45 minute presentation followed by Q&A, or a more informal ongoing discussion as they walk you through their presentation.

The biggest challenge with portfolio presentations is that candidates often struggle to articulate their specific individual contributions and design rationale. When this happens, you'll need to actively elicit that detail, asking the candidate questions like "what was your role?", "who did you collaborate with?", or "was this an existing design system?". They should be able to articulate their specific contributions. This is particularly important for work from large companies, which is likely to be highly collaborative.

Red flag: Absence of product thinking. This usually manifests as an absence of any discussion of user problems, business context, or validation metrics. In such cases, designers often jump directly into feature descriptions and explorations. When this happens, you can prompt with questions like "what problem were you trying to solve?" or "how did you know this was a problem?". These can help you gauge the depth of product thinking, and how well-grounded interaction design decisions were.

Red flag: Everything was quick and easy. Another common red flag is painting the entire process as quick and easy, solved with the first design solution proposed. Although the first option sometimes performs well, the design process is inherently iterative, and should always involve broad exploration, followed by refinement. Candidates should discuss the range of options they considered, and how they landed on a particular decision—whether through user testing, usage metrics, or simply reasoning from first principles based on the available data.

Green flag: Discussion of constraints and trade-offs. Candidates should include a discussion of constraints and trade-offs. Real-world product development is never ideal, and there are always trade-offs made on the basis of cost, time, and complexity. Often the "ideal" solution from a design perspective may take 10x the time and effort to build, and is simply not justified—especially when it hasn't been validated by real world usage. Designers should be able to articulate examples of trade-offs made for various reasons.

Take-Home Design Challenges

Suitable for: Visual Design, Interaction Design, Product Strategy

Take-home design challenges are usually only used where the portfolio presentation is insufficient to get enough signal on the desired skillsets. In most cases, this will mean it's only used for junior designers who have limited work experience and insufficient past work to fill out a portfolio.

This type of challenge will typically take the format of redesigning a particular flow in an app or website. For example, redesigning the onboarding flow for Spotify, or redesigning the Google Analytics home page. The actual challenge should include a realistic brief that includes some basic context and constraints. If you're screening for product strategy, you could deliberately omit validation metrics to see if the candidate proactively highlights the need to define success. However, for junior candidates, you will typically need to at least point them in the right direction.

The challenge should be clearly time-boxed (e.g. 2-4 hours) both to ensure you're making a clearer comparison between candidates' output, and to ensure you're being respectful of their time.

Never use your own product. The only hard rule is that the challenge should never be a flow for your own product or website, or that of a competitor. This will be construed as attempting to get free work done, and it's not uncommon for candidates to vent publicly about this. Some companies even offer a small stipend ($100-200) for challenges if candidates are asked to spend longer than a couple of hours.

After completion, the candidate should present their solution much like a regular past work presentation. This allows you to ask questions about their process, alternative options they considered, and anything else needed to properly screen for the desired skillsets.

App Critiques

Suitable for: Visual Design, Interaction Design, Product Strategy

An app critique involves walking through a popular app with the candidate and asking them questions about it. This is one of the most revealing interview formats because it shows how a designer thinks on their feet and whether they can identify opportunities for improvement in real-world products.

Choose your app strategically. Depending on the level of seniority, you can choose harder or easier options. If the candidate is junior and you're screening them for visual design, you can choose an app which has poor visual design, lowering the bar for them to critique. Whereas if the candidate is senior, you may choose an app that has solid design all around, making it harder for them to provide meaningful critique.

Tailor questions to the skillsets you need:

- For visual design, ask questions about the typography, color, layout, visual hierarchy, and brand expression

- For interaction design, ask questions about the interaction patterns, component choice, and information architecture

- For product strategy, ask candidates how they think the app measures success, or what they would prioritize if they were the product manager of the app

Red flag: Everything is perfect. The biggest red flag here is if the candidate can't critique anything, and says the app is perfect. They should be able to identify issues, explain what else they'd try, and how they'd validate it. For example, when asked about a search mechanism, they may talk about autocomplete, filters, categories, etc.

Green flag: Balanced perspective. Strong candidates should be able to identify the pros and cons of their suggested changes, and have a point of view on whether and how the change should be tested. They understand that every design decision has trade-offs.

Whiteboarding Challenge

Suitable for: Product Strategy, Interaction Design

Whiteboarding challenges are primarily used to understand how a designer approaches the problem-solving process. They're best suited to understanding product strategy and interaction design, and are usually not needed when hiring visual design specialists.

Start with an open-ended prompt. The challenge starts by presenting an intentionally open-ended prompt, such as "how would you redesign the ATM experience?", "how would you reimagine the airport experience?", "how would you design a smart home system?", or "how would you redesign the gas station experience for a world transitioning to electric vehicles?". Note that this doesn't need to be a digital product with a visual user interface.

Time-box and encourage questions. The challenge should last 30-45 minutes, and candidates can and should ask clarifying questions about constraints, business goals, and users before jumping into the solution. It's not expected that they fully solve the problem—it's more about understanding their problem-solving process.

Expect structured problem-solving. A strong candidate will define a clear problem statement, work with you to understand budget and timeline constraints, identify multiple high-level solutions, and have a clear rationale for prioritizing one solution. You may need to encourage candidates to explain their thinking and process out loud as they work through the challenge.

Red flag: Jumping to solutions. Pay attention to whether they follow a divergent-convergent design process and understand impact-based prioritization, or if they jump to a single solution without broader consideration. The latter is a significant red flag that suggests they don't understand foundational design thinking principles.

Green flag: Structured thinking. Look for candidates who break down complex problems into manageable parts, consider multiple stakeholders, and can articulate the reasoning behind their prioritization decisions.

Conclusion

Looking across a combination of these interviews should give you a good sense of each candidate's skillsets. But remember, interviewing is a two-way street, and it's up to you to ensure you're asking the right kinds of questions to get signal across the skillsets you need.

If a candidate has strong visual design in their past work, this may mean the other interviews require deeper probing on interaction design and product strategy. Or if a candidate's past work demonstrates strong interaction design and product strategy, you may need to focus more on visual design in the app critique.

The key is being intentional about what you're testing for and adjusting your interview approach accordingly. A structured process like this will dramatically improve your odds of finding a designer who can actually move the needle for your startup, rather than just someone with a pretty portfolio.

Remember: hiring the wrong designer is expensive—not just in salary, but in lost time, momentum, and the opportunity cost of what the right designer could have accomplished. Take the time to get this right.